Emigrate, yesterday and today:

a docu-film by Alessia Bottone

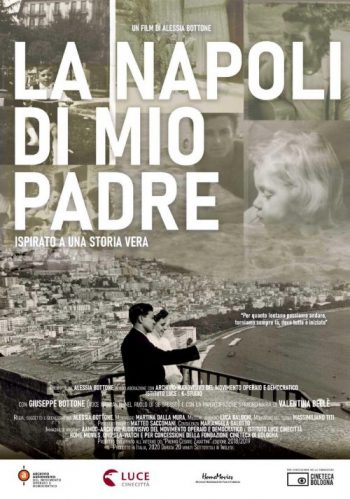

VERONA – What was Dad looking at, from the window? What was he thinking about? Perhaps to his Naples left many years earlier for the “deep” North? To answer these (and many other) questions, the young Italian director, screenwriter and journalist from Verona Alessia Bottone (in the pic below) – with several short films, books, investigations and various awards to her credit – has decided to dig into the past of other lives, those preserved in the audiovisuals from the Aamod, Istituto Luce and Home Movies archives, the Bologna archive that collects family movies. And, mixing those memories with her and those of his father Giuseppe, who moved to the North when emigrating was an odyssey like the one that migrants in search of a better world live today, the docu-film “My father’s Naples” was born: a poignant journey through time. How timely ever!

Alessia, your work is the result of a long search in audiovisual archives that collect “pieces” of lives, lived in anonymity. Why did you choose those videos?

“First of all, because the film was made as part of the Zavattini Prize which involves the reuse of archive material for the making of short films. Being a finalist for the award, I then used the materials made available by the Aamod archive, Istituto Luce and then I went to look for other films in Bologna, in particular at the cineteca and at Home Movies, the family archive. I participated in the call precisely because I had never done a job with archival material and I was fascinated by the possibility of learning this technique also because the award, among its benefits, included the possibility of accessing a training course during which I had way of dealing with professionals in the documentary and archival sector. A wonderful experience that I believe will also determine my next works as I would like to continue using archival material in the future. Of course, it’s not easy: it took me two years to find the images and in my short documentary we find more than 70 films and documentaries, a rather demanding but very satisfying research job ”.

Yesterday’s migrants, like your father, and those of today whom you met while working in a refugees center and whom you cited in the work: what has changed since then for those stories of escape and search? And do you think you will continue to address the same issue in the future too?

“In reality, the issue of migration has always been my fixed point. In 2009 I worked in Switzerland, in a reception center for asylum seekers: I taught reading, writing, dealing with translations and administrative practices and, during that period, I wrote my degree thesis on European asylum policies, a comparison between Italy and Switzerland. I have always dealt with people on the run, I mean the real flight, the one for political, religious, economic reasons, because I think people don’t realize what it means to escape, leave everything overnight, lose everything and not knowing where to go. I lived with those people, so what does it feel like, it takes a lot of courage, all the courage that even the Italians who now live abroad have had, especially those who left between the early twentieth century and the 1960s. It must have been very difficult, settling in, feeling distant, not understanding the language, being discriminated against, as the story in the docu-film. Speaking with some of them, I realize that sometimes they feel much more Italian than us who stayed in their homeland, perhaps because the distance has strengthened that feeling, that need for community that has been crumbling here for various reasons. I admire them a lot, I also lived abroad but in the comfort of the 21st century, it’s different, it wasn’t easy but not that difficult, the atmosphere has changed, luckily not to mention that it is much easier to get a job, a document, open a current account and rent an apartment. If, on the other hand, I think of the new non-European migrants, the discourse changes completely and I am very sorry that the images of these landings, of these children drowning in the sea, these people dressed in rags who face the cold in the Balkans by sleeping in tents. It almost seems that the images have made people addicted, that all this is normal, few are indignant or displeased. Far be it from me to solve an age-old question in a few lines, but history is clear, for centuries we have been moving in search of better conditions. The system has long since imploded, the vaunted social justice has remained a mirage and social inequalities are a constant, people just have to flee in search of a better life ”.

And what about you? Did you ever run away? And why did you come back?

“I am always on the run. And I’ve always been on the run, ever since the teachers asked me to ‘stay seated in my place’. Mine, like my father’s, is not rebellion, but the desire to never stand still, to discover, know, learn, study, confront myself with people. I tried my first escape at 16, but I couldn’t convince my parents: I wanted to go to Germany for the summer to be an ice cream maker and learn German but they didn’t let me, rightly … I was really too much young. But at 21, I won an Erasmus scholarship in Spain and returned… five years later. I graduated anyway, three-year and master’s degree with subsequent Master, but I did it studying from abroad and returning only to take the exams and in the meantime I learned three foreign languages and lived in seven EU and non-EU countries, working and carrying out of training internships. Now I’m in Verona, I’m on break from escaping. I would add that escape is positive, it fosters creativity, it is necessary to feel alive and active, at least, for me it is like that”.

What does your father think of the opera? What did he say to you after seeing it?

“Initially he was a little reluctant, he did not know whether to participate or not as a narrator, he suggested that I contact a professional then he changed his mind. He realized he could do it and, I must tell you the truth, he was really very good. He is not a professional, he acts but on an amateur level, and he worked hard, working on intonation, diction etc. I’m happy to know that my dad, the protagonist of the story, also had the opportunity to tell it in the first person, and then working together was a great adventure, I hope I can do something else with him in the future. He did not want to see the film, until the first screening, at the festival, the Filoteo Alberini di Orte, last August and, judging by his expression, I would say he liked it all right, he was very excited ”

Let’s returne to you: where does Alessia Bottone want to go? What does she dream for herself?

“Alessia dreams of always being amazed, of always wanting to learn and always having faith in the future, I think these are three necessary elements. But, above all, I would very much like to continue doing this job that I love very much, which allows me not to even notice the infinite number of hours I spend at the computer and above all allows me to stop and pause and reflect, a luxury I believe in this historical moment. I’m interested in people, not what they show, but what they think. I like to look for stories, anecdotes and be part of them, thanks to their stories. When you share this with people, you never separate from them, it always remains a connection, a vivid memory, even when you are far away. On where to go… I would say wherever there is something to tell, to discover. I would like to visit a country where time passes slowly, sit on a chair and observe people, what better inspiration for my next job? ”.

Have a safe trip, Alessia.

Watch the trailers here:

La Napoli di mio padre (official trailer)

La Napoli di mio padre (Festival di Napoli)

More Articles by the Same Author:

- Conservatori e Liberali uniti sui progetti di interesse nazionale

- Crombie e Stiles, piani per disabili e senzatetto

- Interferenze straniere, Hogue: “Non ci sono traditori a Ottawa”. Ma ‘bacchetta’ governo e partiti

- Quei 40mila italiani deportati nei campi nazisti

- Il Canada teme un esodo dagli Usa di Trump