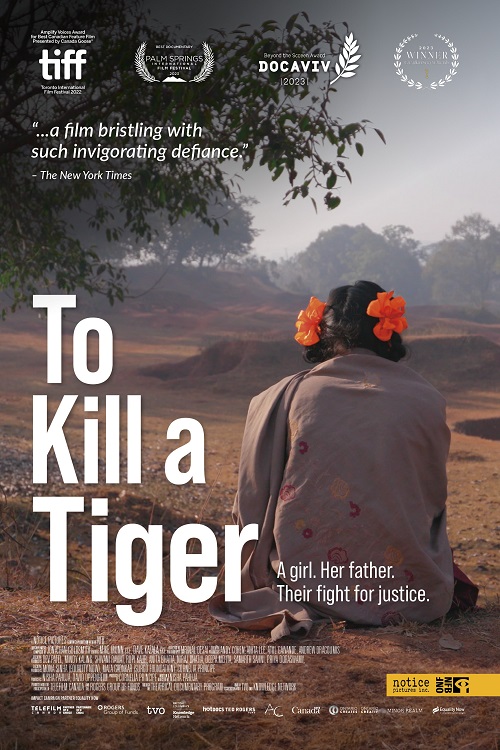

Italian-Canadian Nominated For Academy Award – Best Documentary

TORONTO – One of this year’s Oscar nominated Documentaries, To Kill A Tiger, was produced by Italian-Canadian Producer/Director/Writer Cornelia Principe. A rare feat considering that since 1929 only fifteen Canadians have been nominated in the category. The fine art to making a poignant documentary often hinges on how well the filmmakers execute their journalistic integrity with their ability to tell a story. In the case of To Kill A Tiger, filmmaker Nisha Pahuja documents a local story, but one that is echoed throughout the country. Her challenge is to report on a specific crime while telling a larger and more tragic story.

To Kill A Tiger follows the harrowing fourteen-month journey of Ranjit, a father seeking justice for his thirteen-year-old daughter Kiran, who was gang raped by three villagers. The accused had dragged her away from a family wedding, brutally raped and assaulted her, and threatened to kill her if she told anyone. Pahuja however, focuses less on the court’s landmark conviction of the accused and turns her attention over to the country’s “way of thinking” – specifically on gender relations. Her cameras follow Ranjit and his lawyers as they speak to everyone from the Mukhiya (District Chief) to the villagers. Although most admit to the crime, few if any want the accused jailed. The Mukhiya tells the victim’s father, “what’s done is done, think before you act…for your own protection”. He even suggests that Kiran be given in marriage to one of her Rapists. When Kiran’s lawyers seek testimony from the Village Ward Member, she’s told, “No one person is more important than the Village”, later adding that seeking justice is futile as, “There are plenty of Rapists out there to deal with”. Even more telling was the Defense Attorney’s commentary: “This is not the West, here I can’t even trust my own son…why was she out after midnight dancing with her friends?” This is the sentiment caught on camera in a Nation where statistically a woman is raped every twenty minutes.

Pahuja’s To Kill A Tiger champions a father’s resilience and determination to “stand by his daughter”. For fourteen months, Ranjit and his family were harassed and threatened by villagers – warned even that his house would be burned down. To call this “antiquated” would be to grossly undercut the problems facing some women in India, and this is something Pahuja’s film effectively conveys. Angry mobs eventually eject Pahuja and her cameras from the Village, also warning the Srijan Foundation Workers to stay away. Thankfully, the Villagers’ efforts were defeated. The courts eventually sentenced each of the accused to twenty-five years in jail, the longest ever jail sentence given for a rape charge in the region. Her triumph in court captures Kiran’s first smile on camera, but even more effulgent were Kiran’s following words. Abandoned and derided by her townspeople, branded as “stained” and “unmarriable” and left virtually imprisoned in her home after being raped and assaulted by three men, Kiran tells Pahuja: “We weren’t born to walk the wrong path…whatever you do with an honest heart always turns out good”. Of her father she says holding back the tears, “I want him to stand by me through think and thin. Those who walk with their steps in unison never fail”.