First the shame, then

the pride of being Italian

Seventh chapter of the publication, in ten chapters both in Italian and English, of the academic presentation that our periodic collaborator Goffredo Palmerini held in L’Aquila on November 3rd, on the occasion of the CRAM Assembly (Regional Council of Abruzzesi in the World). The report is entitled “Historical notes on Italian emigration” and traces the history of the Italian Diaspora.

L’AQUILA – (continued… part seven) Almost immediately after the Second World War, the departures “picked up from where they had left off”, but with different employment objectives. Because after the Second World War, those who left already had a job, they were artisans and perhaps even had a higher education qualification than an elementary school one. Those who visit Argentina today, especially the big cities – as happened to me in my four trips to that great country, precisely because half the population has Italian origins – have the impression of being in a European city, sometimes even of being in an Italian one. We see it in people’s tastes, the way they converse, the way they behave so typical of the Italian style, of our way of life.

Examples of our exodus is seen elsewhere. The third country in terms of number of Italians (emigrants of various generations) is the United States of America, with over eighteen million citizens of Italian origin. The United States has had a very complex attitude towards Italians. Today, we celebrate the beautiful aspects of Italian emigration, but there is a painful component which is terrible. Much of this tale of suffering – replete with prejudice, stigmas, even contempt – relates to the attitude of Americans towards the Italian immigrants of the first wave of migration. Often, they treated Italians as “inferior people” – rough, dirty, uncultured, prone to violence – and with derogatory epithets (dago, guinea, etc.).

Just imagine that after the approval of the law authored by President Lincoln to abolish slavery, Italian emigrants replaced the Black slaves who left the cotton fields in Georgia, Florida, Mississippi, Louisiana and other southern states. Sometimes they suffered actual lynchings, as happened in New Orleans in 1891 and Tellulah in 1899.

Our emigrants went to the Southern states, in the same way as they flocked to the coal mines of West Virginia (Monongah, 1908), Pennsylvania, Arizona, Colorado, and, above all, to the large metropolitan and industrial areas of New York, Philadelphia, Pittsburgh, Boston, Chicago and Detroit. Italians were viewed very negatively, with prejudice. There were those who looked at them with suspicion, and I am not referring to the rotten components of Italian society, an extremely small minority, the criminal element linked to the mafia and the black hand.

I am talking about the vast majority of Italians in America who sweated blood and tears to build a future for themselves, sometimes suffering all sorts of indignities, at least until the latter part of the twentieth century. It is enough to read some novels of the time, even by some from Abruzzo – Pascal D’Angelo or Pietro Di Donato, or even by a great American writer like John Fante – to clearly understand the stigmas of which Italians were victims.

Also found in these stories is the reason Italians have often Americanized their name and surname, so as not to be recognized, so as not to suffer harassment. For many decades they avoided declaring their origins, unlike the pride they now show. Only from the 1930s did this pride slowly begin to manifest itself with the first Columbus Day parades in New York. As an event, a happening, it was inspired and begun in 1929 by Generoso Pope (Generoso Antonio Papa, an Italian American magnate of Irpinian origins). It has since become a national holiday commemorating Italian pride in the States.

The stigmatization of Italians diminished only in the second half of the 20th century, but, until then, there had been this intensely negative disposition towards us.

In the last thirty years, thanks to changes in the data requested in the national census, it has become possible to ascertain just how many Italian expatriates or people of Italian origin live in the United States. Once the prejudices of “officialdom” started to be stripped away, our compatriots began to declare their origins in massive numbers. This has brought our numbers to the 18 million mark of those who, in America, trace their origins to our native land. Yet, studies suggest that number may be significantly higher.

(continues…)

Translation in English by the Hon. Joe Volpe, Publisher

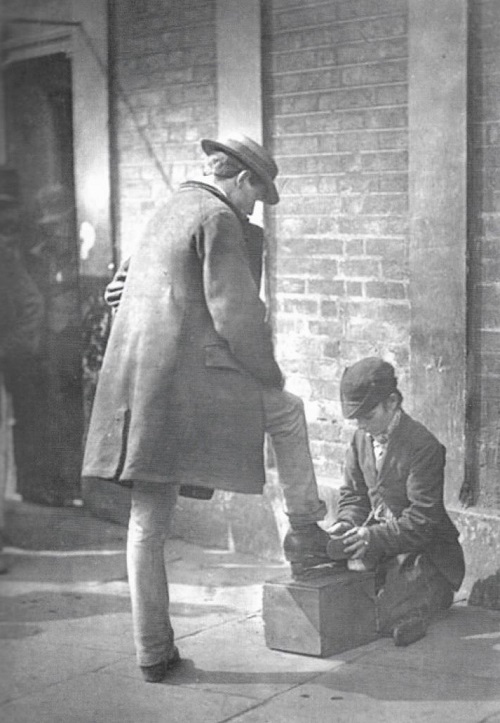

The pic at the top of the article is “Lustrascarpe” from the book “La Merica. Emigrazione dei Monteleonesi verso gli Stati Uniti dal 1882 al 1924” by Antonio De Vitto