Enea, A Tragic Roman Tale

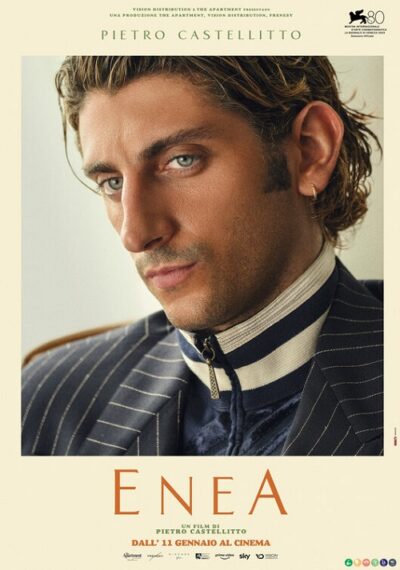

TORONTO – Pietro Castellitto’s “Enea” could be interpreted as a subversive allusion to Virgil’s poem The Aeneid, but set in modern day Rome. The film’s title character (Enea) is a young man journeying through the city’s decadent underworld in a quest to establish himself, but begins his story where Virgil’s tale ends. Contrasting Virgil’s Aeneas who rose from the ashes of Troy, Castellitto’s Enea finds himself eroding within a world that seems doomed to collapse.

The film’s photography is at times mesmerizing, highly [and purposely] stylized and is a meaningful attempt to capture Rome through unique vantage points, ranging from aerial to blurred long shots and reflected through glass and mirror. The only trace of ruins comes from the unravelling of the lives within Enea’s circle. Castellitto paints a new-look Rome whose inhabitants struggle to measure up to the city’s grand legacy.

Perhaps as a Roman native, Castellitto is contemplating what it’s like to live in the shadows of Ancient Rome. Enea’s newly licensed pilot friend Valentino, when asked what his purpose is, best illustrates this sentiment: “Rome looks like a concentration camp from the sky. It looks so small that I could take it in my hand. This is my purpose”.

“Enea” opens with a conversation about hope and consequently purpose, which acts as a springboard into a colourful and chaotic two hours. Enea is a Gatsby-like figure, though unlike Gatsby he’s born into privilege. He has ample charm and intelligence to create an empire but lacks the ambition and desire to do it through honest channels.

Castellitto ditches a rigid plot, favouring instead to interweave and intersect the lives within Enea’s world, each contributing to his fate, and each harbouring their own secrets and despairs. His father, a troubled Psychiatrist, his mother a depressed TV Presenter, a brother with arrested development and a parentless friend. “Enea” is the story of a man disconnected from society, his family and the consequences of his actions, but on the road to ruin he discovers purpose – through a woman.

Castellitto’s work as writer/director is commendable though not entirely fashioned for a general audience. His meandering camera reveals characters and their environments in unsuspecting ways, sometimes jolting but simultaneously artful and symbolic. The film is layered both in terms of story and craft, and above all imprints a lasting image of the visual experience. It’s a Rome rarely depicted in cinema.

Pietro Castellitto: “I like movies that are morally unpredictable, and to make or do that you have to sometimes follow the inertia of life which can teach you a lot. Life, if we stare it in the face, can sometimes offer amazing suggestions”. It’s no wonder he wrote a character that does the opposite. A prompt perhaps for the viewer, to rise from Enea’s ashes.

Massimo Volpe is a filmmaker and freelance writer from Toronto: he writes reviews of Italian films/content on Netflix