Caravaggio’s Shadow: Il Tenebroso

TORONTO – One might convincingly posit that Michele Placido’s film about Michelangelo Merisi of Caravaggio is a work worthy of the Baroque Artist’s approval – were he alive today to view it. Of course, one will never know, and to expect to capture the full context of a man’s life through a two-hour account, four hundred years removed, is both absurd and impossible.

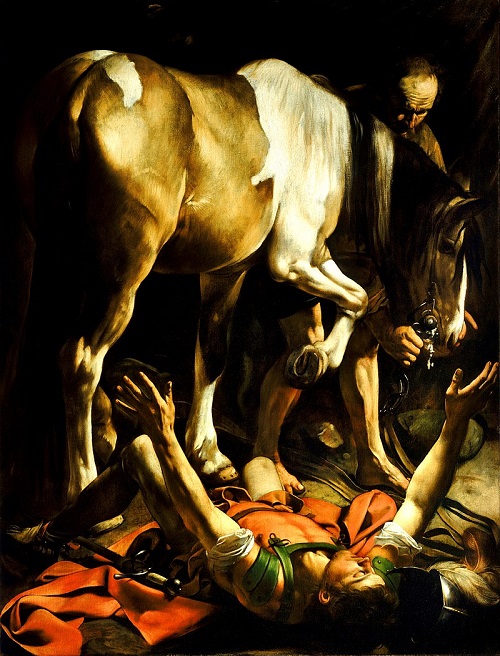

With “Caravaggio’s Shadow” however, Placido paints a compelling depiction of the man by borrowing one of Caravaggio’s core principles: to find the real. Caravaggio brought the miserable, the poor or what the disapproving authorities deemed “abject Beings” into his paintings, by employing them to model for his biblical representations. It’s possible that Caravaggio may have believed that if he could make a Madonna out of a courtesan (Lena Antonietti), he could help awaken the divine in all of us. This was the collision between the light and darkness, the chiaroscuro, which not only defined his work and masterpieces, but his humanity.

The screenplay’s clever conceit, imagined by co-writer Sandro Petraglia, is its fictional character named “Shadow” – a Priest hired by the Holy Office to investigate Caravaggio’s alleged crimes. Effectively giving the film its title, the Shadow, among other things, serves as a parallel between Caravaggio’s “ignoble” exploits and the Church’s covert operations.

The film’s story begins in 1609 as Pope Paul V summons his “Shadow Man” to Castel Sant’Angelo and orders him to “investigate the paintings that flout the sacred representations in our churches”. The impetus for the investigation: Caravaggio’s Noble Friends and church benefactors request a Papal pardon for a homicide Caravaggio committed in self-defence. A determined Pope Paul V, as imagined in the film, orders a thorough investigation into the personal life of the recalcitrant painter.

Among the historical Michelangelos, Merisi and Buonarotti, more is surely known about the latter, as Merisi’s transgressions unequivocally played a role in the concealment of his artistic legacy – one that grows larger with every new exploration into his life and works.

Caravaggio’s commitment to representing things as they are in nature, dark and often frightening, has been argued to be the forerunner to modern art. Placido, during a recent Masterclass even suggested that if Caravaggio were alive today he might not be a painter, but a “war photographer on the front lines, capturing the battle”.

Caravaggio’s chiaroscuro portrayed his subjects in a new light both literally and subversively through his defiant messaging. He was a shining example that there are often profound principles shared in dissemination through artwork, and that the Artist wields a magnificent power to elucidate and enrapture.

“All remained speechless and mute, breathless as they stood in front of Merisi’s work”, explains a church beggar to the interrogating Priest in the film.

I can attest to this sentiment having seen ten Caravaggio originals when Ottawa’s National Gallery featured his work back in 2011. What was evident even to my then uninitiated and uneducated mind was the immense genius of Caravaggio’s talent. His artwork’s immediate effect felt akin to being let in on a secret. Perhaps Placido’s film can initiate a new generation of art enthusiasts and truth seekers, or even reignite the curiosity of those who once vigorously pursued the wisdom of the ages – be it through religion or art.

Having been nominated for five David Di Donatello Awards in 2023, the film more than warrants a watch – not least for the opportunity to enter into Caravaggio’s shadowy and seductive world for two hours. And when the screen fades to black, as it once did for this glorious Painter, you too might be open to what Caravaggio believed exists: “infinite worlds, infinite skies, infinite universes and the infinite divinity that lives in everything”.

Massimo Volpe is a filmmaker and freelance writer from Toronto: he writes reviews of Italian films/content on Netflix