TORONTO – Organ donations help save lives.

On Monday, Nova Scotia became the first jurisdiction in North America to enact the policy of “presumed consent” for organ donation. Under the Human Organ and Tissue Donation Act, all eligible adults in Nova Scotia are considered potential organ and tissue donors after death. According to the new policy, it is referred to as “deemed consent”, unless individuals choose to register their decision to “opt-out”.

Those who are not eligible for deemed consent are people under the age of eighteen, those without decision-making capacity and people who have lived in Nova Scotia less than twelve months.

Changes like this do not happen quickly. The legislation first passed on April 2019. It took roughly 20 months of planning and work to ensure provincial systems were equipped to handle the change.

There is good reason for the change. One donor can save up to eight lives through organ donation. Additionally, that one donor has the potential to enhance the lives of up to 75 people through the gift of tissue donation.

Yet, despite the life saving gifts one donor can make, Canada still has a shortage of organs. According to Canadian Blood Services, at the end of 2019, over 4,400 patients were waiting for transplants. The wait can be long and painful; many patients wait years for a second chance at life. Sadly, some will never get the opportunity. In 2019, 250 Canadians died while waiting for a transplant, up from 223 in 2018.

In Ontario, the system works differently. Roughly 35% of the population are registered donors. This is good, but it could be better. As of September 2020, about 1,600 Ontarians were waiting for an organ transplant.

The Covid-19 pandemic has not helped the situation. For instance, in 2020, at one of the top five multi-organ transplant programs in North America, there was a 20% decrease in activity.

Dr. Atul Humar, Medical Director at the University Health Network’s Ajmera Transplant Centre, said medical staff performed 558 organ transplants at the centre in 2020, down from 701 the year prior. He attributed the change to a “drop in donor organ availability and reduction of surgeries during the first wave the pandemic”.

The concern is that more patients will suffer during this second wave as some surgeries are being cancelled to free up capacity in hospitals.

Dr. Humar adds reassuringly, “transplant is one of the services prioritized during Covid-19 restrictions as there is a provincial guidance not to waste life-saving organs that become available”.

As for Ontario adopting a similar legislation like Nova Scotia, there are no plans yet. Dr. Humar says it is a great initiative adding, “we hope that Ontario legislators and policymakers consider this option”.

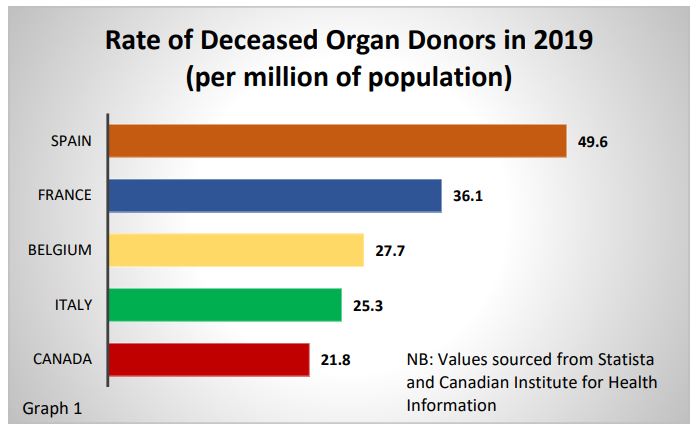

Other European countries such as Spain, Belgium and France have experienced increases by as much as 35% after adopting a presumed consent system. When attempting to explain Spain’s success rate of 49.6 deceased organ donors per million population, it is the presumed consent system that is perhaps cited most often (graph 1, above).

As in any circumstance, change takes time. The effectiveness of such change in legislation and systems require a combination of other initiatives. Together this will help create an overall culture of organ donation.